Rare Earth Wars – China’s Mineral Power Play Triggers a Global Scramble

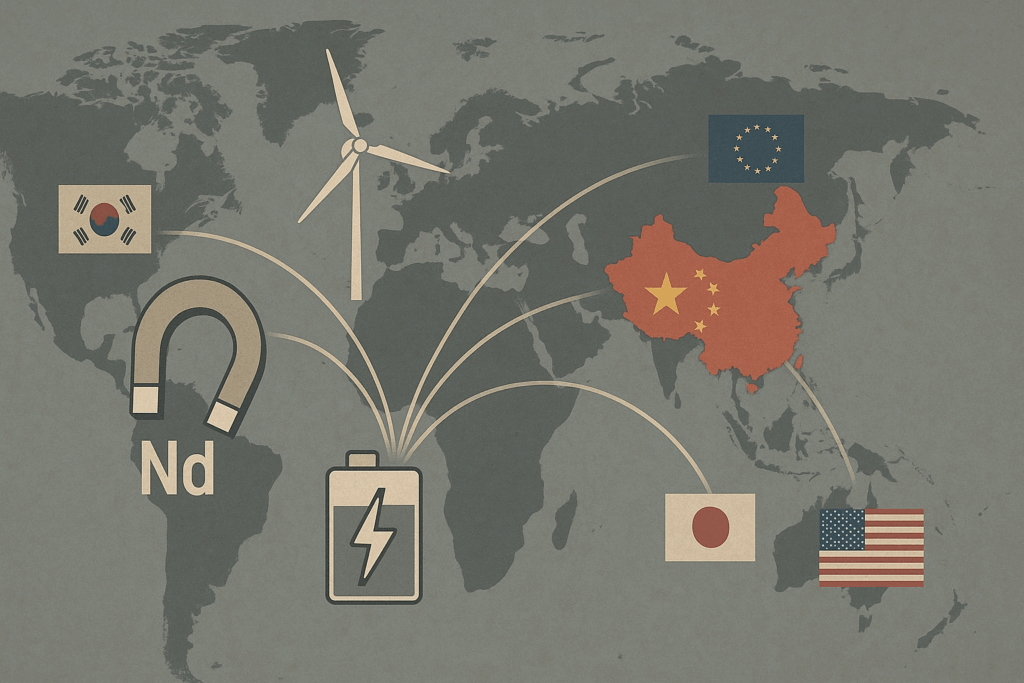

In recent months, China has tightened export controls on several heavy and medium rare earth elements, imposing a new licensing system that has slowed or paused shipments of samarium, terbium, dysprosium, and others. Beijing presents the move as a routine measure to safeguard strategic resources, whereas trading partners view it as a reminder of the world’s reliance on China’s processing capacity. The immediate result has been higher prices and lengthier lead‑times, prompting manufacturers from Europe to North America and across Asia to reassess inventories and diversify supply chains.

China’s 25‑Year checkmate on critical minerals

China’s latest restrictions did not come out of the blue – they are the culmination of decades of strategic planning. Over the last quarter-century, China methodically built up a domestic and global rare earth empire. It consolidated dozens of mines into six big state-run groups, mastered the dirty work of processing these metals, and invested in overseas deposits from Africa to Asia. Beijing now holds a stranglehold on rare earth supply chains, especially for the heavier, more specialized rare earths.

By 2023, China was responsible for roughly 90% of the world’s refined rare earth output and an astonishing 99% of processing for the hardest-to-refine “heavy” rare earths. As one Chinese commentary proudly put it, China followed a steady “gradual strategy” – prioritizing long-term gains over quick wins – and “used 25 years to gain a firm foothold in the global mining sector”. The United States, Australia, and the European Union are racing to catch up through new mines, recycling programs, and subsidies for magnet plants, yet most projects are years from full capacity.

Seven Elements Under Lock and Key

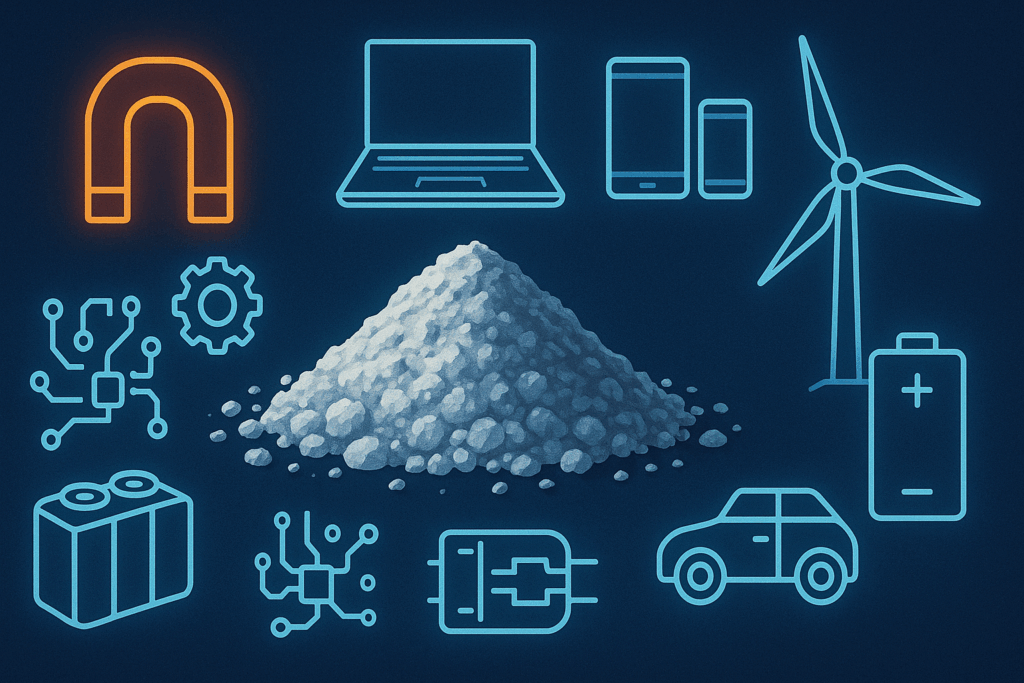

China’s export curbs specifically target 7 out of the 17 rare earth elements – primarily the medium and heavy rare earths critical for high-tech applications. Here are the seven “magnificent metals” caught in the crossfire, and why they matter.

- Samarium (Sm): A medium-weight rare earth used in specialized magnets (samarium-cobalt magnets) that can withstand high temperatures. Samarium magnets are found in precision-guided missiles and aircraft engines, and samarium is also used in nuclear reactor control rods and infrared optics.

- Gadolinium (Gd): A heavy rare earth prized for its magnetic and neutron-absorbing properties. It’s a key ingredient in MRI contrast agents for medical imaging, and in certain defense applications like thermal control systems and sensor technology. Gadolinium can also be alloyed with metals for high-strength, high-temperature materials.

- Terbium (Tb): A heavy rare earth essential for high-performance magnets. Just a sprinkle of terbium can dramatically raise a magnet’s operating temperature, which is why it’s used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators, and military drone actuators. Terbium is also used in green phosphors for lighting and displays.

- Dysprosium (Dy): Another heavy rare earth that is the secret sauce for neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent magnets. Dysprosium allows magnets to remain stable at high temperatures, making it critical for EV motors, robotics, and aerospace guidance systems. Without dysprosium, many cutting-edge motors and generators would literally lose their magnetism when things heat up.

- Lutetium (Lu): The heaviest rare earth, used in smaller quantities but no less important. Lutetium is found in PET scan detectors, high-refractive-index glass, and catalysts for refining petroleum. It’s also used in some X-ray and gamma ray detectors. China’s dominance means alternatives for lutetium supply are extremely limited globally.

- Scandium (Sc): Often lumped in with rare earths, scandium is used to create super-strong, lightweight aluminum-scandium alloys for aerospace components and 3D printing. It’s also used in solid oxide fuel cells. Airliners and rockets benefit from scandium alloys, and the metal’s rarity (small global output) means any Chinese export control causes immediate scarcity fears.

- Yttrium (Y): A versatile element used in laser systems, camera lenses, and smartphone screens. Yttrium is crucial for yttrium iron garnets in microwave communications and for phosphors that make LED displays red. It’s also used in high-temperature ceramics and as an additive in alloys. Like other heavy rare earths, China produces the lion’s share of the world’s yttrium supply.

Together, these seven elements are indispensable for the magnets and materials at the heart of modern technology. They end up in everything from the electric motors in cars and drones to the guidance systems of missiles and the sensors in smartphones. By tightening its grip on these specific elements, China isn’t just blocking raw ores – it’s also restricting the export of rare earth magnets and alloy products made from them.

Can the World Live Without China’s Rare Earths?

China still refines about 90 % of global heavy rare‑earth output, and no other country yet has a full mine‑to‑magnet chain. New U.S. and Australian projects—MP Materials’ Texas magnet plant, Lynas’ heavy‑REE facility, Browns Range in Western Australia—are years from scale, while Brazil, Vietnam, India, and Africa are only beginning to build separation capacity. Recycling and rare‑earth‑free motor designs (e.g., Tesla’s next‑gen induction motor) help but cannot close the gap soon. Even if every announced project succeeds, analysts estimate non‑Chinese supply could cover only 25–30 % of world demand by 2030, leaving most industries dependent on Beijing’s licensing decisions.

Global Shockwaves Beyond the U.S

China’s April 2025 license rules apply to all importers, so Europe’s wind‑turbine and EV sectors, Japan’s precision‑machinery makers, and South Korea’s electronics firms all face longer lead times and rising prices for dysprosium, terbium, and other heavies. The EU has invoked its Critical Raw Materials Act to co‑fund new mines; Seoul doubled strategic stockpiles; Tokyo relies on a one‑year reserve and Lynas contracts. On the logistics front, bottlenecks have emerged at Chinese ports. As mentioned, any rare earth shipments that hadn’t cleared customs by early April were stopped in their tracks.

Warehouses in ports like Shanghai and Lianyungang are stuck holding magnet shipments and oxide powders, waiting for paperwork that may or may not come. Some Chinese suppliers are reportedly in limbo, unsure if and when they’ll get export licenses, which makes it impossible for them to guarantee delivery to foreign clients. This prompted several Chinese exporters to invoke force majeure, essentially saying “sorry, we can’t fulfill the contract due to government action”.

The longer this drags on, the more overseas manufacturers – be they automakers in Germany or wind turbine producers in Spain – might have to slow production for lack of key inputs. In Germany, which has no domestic rare earth sources, industry groups have raised alarms that the Chinese controls could hit their advanced manufacturing sector (from automotive to robotics) unless alternative sourcing is found.

The New Battlefield of Tech and Trade

The “Rare Earth Wars” highlight the interplay of geopolitics, economics, technology, and industry. It’s geopolitics in that access to these elements can tilt the balance of power; it’s economic because it affects global trade and pricing of countless products; it’s technological since our most advanced innovations depend on materials that are suddenly scarce; and it’s industrial because whole sectors (automotive, aerospace, electronics, green tech) must adapt or falter based on materials supply. In a way, these humble rocks and ores have become as strategically significant as microchips or oil barrels.

As this saga unfolds, one thing is certain: the age of innocence in critical minerals is over. No one can take supply for granted anymore. Countries are drawing up battle plans – be it investment strategies, stockpile buildups, or diplomatic deals – to secure these resources. China, having planned its rare earth dominance decades in advance, is now leveraging it to the hilt. For the rest of the world, the choice is clear: develop new supply chains or remain at the mercy of Beijing’s policy whims.

In the end, the “Rare Earth Wars” won’t likely produce a surrender ceremony or peace treaty, but they will undoubtedly redefine how the world sources the elemental building blocks of our high-tech future. And if nothing else, people far and wide are now learning how to pronounce dysprosium and yttrium – perhaps begrudgingly so, as they realize just how critical those oddly named elements have become in the grand chessboard of global trade.

Source: https://thebulklab.com